CITY ARTS, FEB 2017

In Your Eyes

The liberating glamour of Mary Anne Carter

by Amanda Manitach

City Arts Magazine, February 2017

Cover photo by Megumi Shauna Arai

On an overcast day in December, Mary Anne Carter enters Pratt Fine Arts Center’s print studio with an oversize, virgin silkscreen under one arm, her slight frame drowned in an equally oversize sparkling gold sweater. Draped over her other arm is a dainty leopard-print handbag and a smock spattered with neon ink.

Carter, 28, spends at least 30 hours a week in the gargantuan Central District studio, embellishing textiles with messages, turning silk underwear into wearable broadsides, emblazoning shirts and scarves with biting feminist poetry. In a workday ensemble finished with black tights, a felted vintage pillbox hat, and with yesterday’s glitter icing her eyebrows, Carter looks a little Edith “Little Edie” Beale and a little Edie Sedgwick, with an aura of club kid clinging to the edges.

In 2017, it’s outmoded to begin a story about a female artist by describing her looks. But in Carter’s case, the outré wardrobe is a reflection of the soul—a carefully crafted image aligned with the self-prescribed “strict no boredom policy” advertised across her website. Carter’s artistry is holistic, encompassing everything from her sexuality and politics to her sartorial choices and product line. Tying it together is a signature sense of provocation that unapologetically assimilates femme queerness and traditional feminine glamour.

“Most of my work chips away at the patriarchy and more serious political topics through humor,” Carter says, tying a smock around her waist and preparing her screen for exposure in the nearby darkroom.

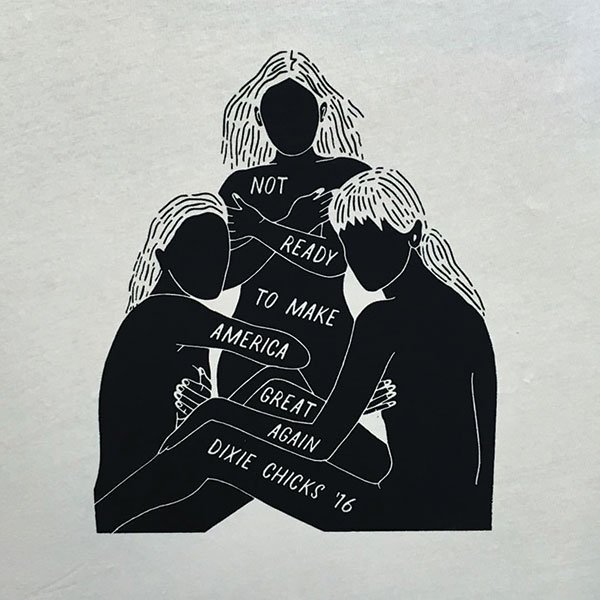

Since launching in July 2016, Carter’s line of femme-forward unisex tees (including her popular design targeting the sexist phrase “resting bitch face,” left) are among her best sellers. Hand-printed broadsides and prints riff on sexual innuendos, poetry and the Dixie Chicks, one of Carter’s favorite bands.

Carter’s most in-demand designs—sold via her online store, jesusmaryannejoseph.com—are gentle, defiant one-liners layered with meaning. One simple line drawing depicts a hand, middle finger raised, clutching a compact engraved with the words “THIS BITCH FACE DOES NOT REST.” Another, “Femme Manicure,” shows a clenched fist with talons. Since launching her website last summer, she’s sold more than a thousand such items.

“There’s a lot of discussion within the queer community about the visibility of femmes,” Carter says. “Thinking about this gave way to my playful femme collection, which glorifies my iteration of a femme manicure—perfect long nails except for two very ratchet index and middle fingers—it’s a dick joke about fingering. As a project, it’s both fun and necessary.”

Other items in production: shirts adorned with butts (an homage to beloved gay bar Pony), pots of “long-lasting, non-flaking, dense-as-can be” Holy Hairdo hair glitter (which she currently formulates and manufactures herself) and a tote printed with a pentagram, pizza slices, hot dogs and a portrait of David Bowie. (“It’s about time someone put everything good and holy on the same tote!” the online product description states matter-of-factly.)

“I want people to embrace themselves, just be them,” Carter says. “I try to embrace me and be me in everything I do. Hence the glitter and googly eyes and things that definitely aren’t chic by most standards.” It’s true: Departing from even the most experimental fashion, Carter regularly adheres googly eyes to her face.

“I like how divisive glitter is,” she says. “People hate it because it gets everywhere. I think glitter is the least of our problems. It goes with everything!”

Carter’s approach has resonated with fans, as she has taken on a role as unlikely style icon in a world awash with cookie-cutter, audience-seeking models. Carter credits her success to her mantra of risk-taking.

Her infatuation with childhood adornments started as a way of gilding an “imperfection”: Beneath the traces of gold flakes that cling to the apple of her cheek, there’s an expansive birthmark, a merlot-colored starburst that spangles part of the right side of her face. Because it’s so close to her eye, Carter faces serious potential health risks; port-wine stain birthmarks are on their own benign, but when occurring on the face, they’re often are paired with the Sturge-Weber syndrome, which causes glaucoma, seizures, headaches and other issues. As a result, Carter spent an inordinate amount of time in surgery as a kid, undergoing more than a hundred treatments. By the age of 10 she was combatting glaucoma.

“Having a birthmark expanded my view about the opportunities of expression. I never held myself to looking like everyone else,” she says. “Instead I would wear sequined shoes and glitter. In middle school when everyone was trying to blend in, I started thrifting things like chopped-off wedding dresses. People would ask me what happened to my face every day, with mixed reactions. I realized early how physical appearance affects you and how you can harness that.”

Carter grew up in conservative Charlotte, North Carolina, with a father who worked in banking and a stay-at-home mom. She and her family spent summers visiting her grandparents in New Mexico, exploring the desert ruins and ghost towns of the Southwest—a welcome reprieve for a girl who spent the balance of each year attending Catholic school, dressed in a uniform.

In high school Carter—often pegged as subversive for the way she dressed—wasn’t into hip music, drinking or drugs. One thing she did pick up young was screenprinting, which she learned at 10 and never quit.

Though she loved making art throughout childhood, Carter opted to study journalism at Virginia Tech, eventually branching out into marketing. During a year abroad in Amsterdam, she fell in love with the idea of a smaller city with big culture. Carter had visited Seattle when she was 15. “It was the first city I went to where I felt, these are my people, these are my tribe.” She tucked that observation away in college and ended up moving to Seattle in 2011, two weeks after graduation.

Soon after her arrival, Carter settled into her role as outreach coordinator at Second Use Building Materials, an architectural salvage yard in SoDo where she handles marketing, design and special events. She occasionally takes on an outside design project, but her focus is on her own rapidly growing product line, which she started last year as a way to make art in a form that was accessible to a wide audience and not cost prohibitive. T-shirts were a practical canvas. Now Carter’s screenprinted items are carried in seven boutiques as well as on her website.

Carter views this collection as a sort of gift shop that will fund and pave the way toward future work that’s more in a couture direction, as well as installations that integrate art and costume. One of her goals in 2017 is to secure a permanent gallery space in which to feature her own and others’ artwork, as well as to host events. (Carter curated an art gallery in Blacksburg, Va., throughout college, and in August 2015 attempted to launch a gallery called Fashion Hotdog 225 out of her then-apartment, but a crowd of more than a hundred viewers spooked her landlord, causing it to be both first and final Fashion Hotdog event.)

Her last five years in Seattle have marked an evolution that transformed childlike costuming into a sophisticated statement about the world through Carter’s eyes, not least of which is the role of fashion and commerce in the normalization of sexuality.

“The binary version of gender is so sad to me,” she says. “I hate how society forces the sexes to war; it’s woven throughout so much of our commercial products, our advertising.”

Carter was 25 when she came out. Growing up in Charlotte, she knew few women who were out; as a self-censoring Catholic, she never allowed herself to think about sex, let alone sexual preference. “That’s the kind of harm conservative values can do—they can cause estrangement to yourself as a person,” she says. “Living in Seattle, I finally identified as queer and hung out with the queer scene but didn’t feel the need to talk to my parents about it. Now a big MO of mine is to be out and be yourself, and to feel pride in that—pride that isn’t contrived.”

Today Carter often collaborates with her girlfriend, writer Sarah Galvin (a City Arts freelancer), who reignited Carter’s interest in poetry. Their joint projects include productions such as the annual “Least Boring Poetry Event of the Year,” where revelers annihilate poetry-emblazoned piñatas and writers wax confessional with readings under party lights. Carter also illustrates Galvin’s “Watch This” column in Jetspace Magazine.

Carter prefers the handprinted broadside as common ground where image meets text. Produced from the 16th to the 19th century, broadsides were originally cheap, ephemeral throwaway media: one-sided flyers printed with songs, rough drawings, proclamations of hangings or advertisements for the latest cure-all. Carter’s contemporary screenprinted broadsides are exhibited in art galleries, offering a broad interpretation of and departure from their historical predecessors. They splash Rich Smith’s poems across crinkled sheets of iridescent paper or mimic the old-timey script of the Wild West while proclaiming Galvin’s scalding 21st-century wit. In step with her philosophy on art, Carter is emphatic that poetry should never be boring, inaccessible, undecipherable.

“I think people are drawn to my work because it feels like a permission slip to be playful and bold,” she says. “Whether or not someone identifies as a femme or a bitch or whatever, people identify with the message to be loud, creative, over-the-top. My use of glitter and googly eyes is in deliberate opposition to seriousness in a time when everything is so damn serious.”

One of Carter’s prints is a self-portrait in the form of an articulated paper doll with her own birthmarked face, a witchy hat, a turban and a cob of corn for good measure.

“We’re taught to outgrow things—certain art materials, like pompoms, pipe cleaners and glitter,” she says. “We’re trained to trade in color and playfulness and imagination for booze and drugs. Then we’re supposed to trade in these vices for settling down and getting a house. But what happens if we go through life on a different timeline, not ditching things along the way, but assimilating, building on them, living in moderation?”

In March Carter will apply her mojo to new mediums for City Arts’ Genre Bender, collaborating with dancer/choreographer Dani Tirrell, who shares her appreciation of all things sparkly. Carter is making costumes, props, short films and sets for the performance.

“[Dani and I] wanted to make a piece that was an energetic and humorous break from the bleak political climate,” Carter says. “Our central theme is exploring the root of normative culture and beauty/lifestyle standards that repress self-expression—but in a lighthearted, visually striking, straight-up weird way.”

For Carter, “normal” is a loaded word. “There isn’t anything inflammatory or ironic about doing what makes one comfortable and happy,” she says. “My obsession with craft supplies and with the ugly, tacky and absurd is an opportunity for dialogue about why self-expression is important.”

For her, there is no limit to who you can be. “I’ve always been obsessed with these larger-than-life caricatures of people, which is why my dad says I don’t know the difference between costume and outfit. I don’t think you have to choose. You can be something different every day. Owning your differences is what makes you interesting.”