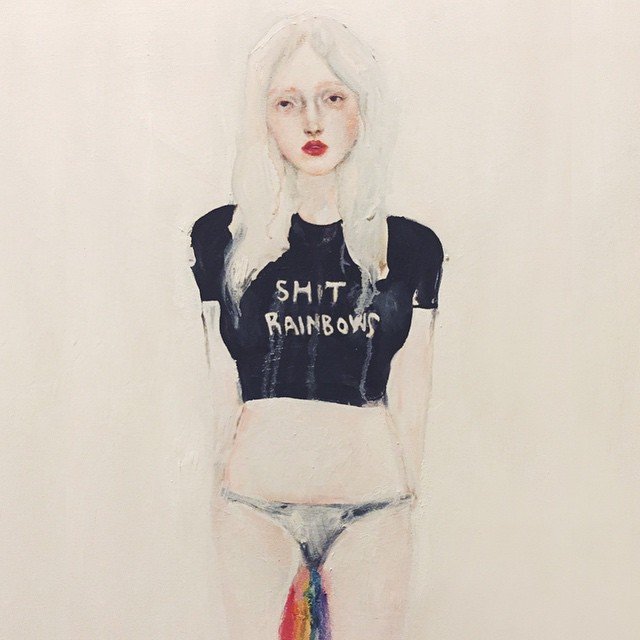

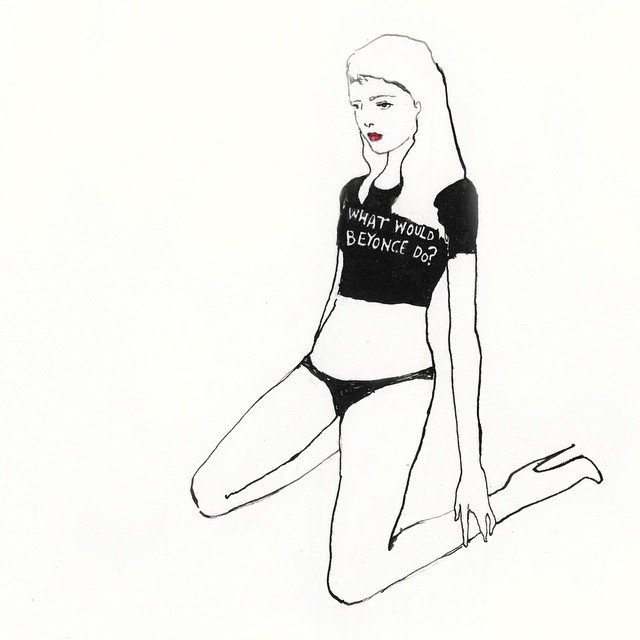

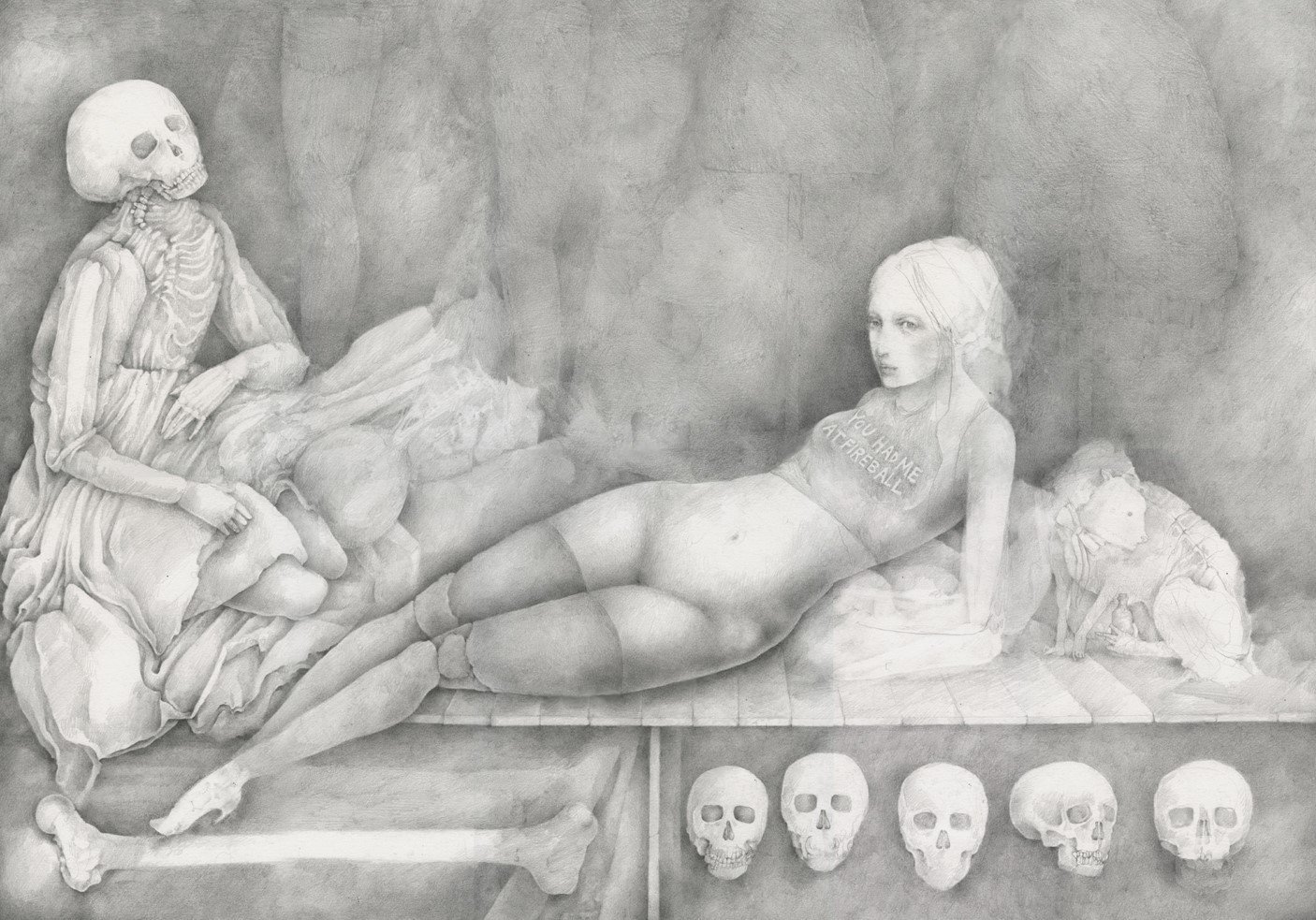

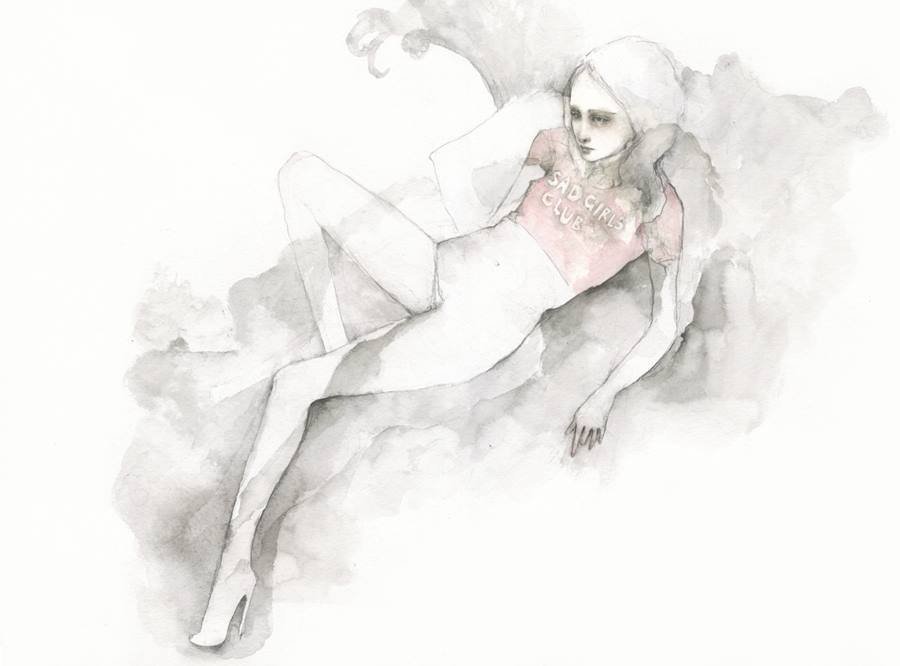

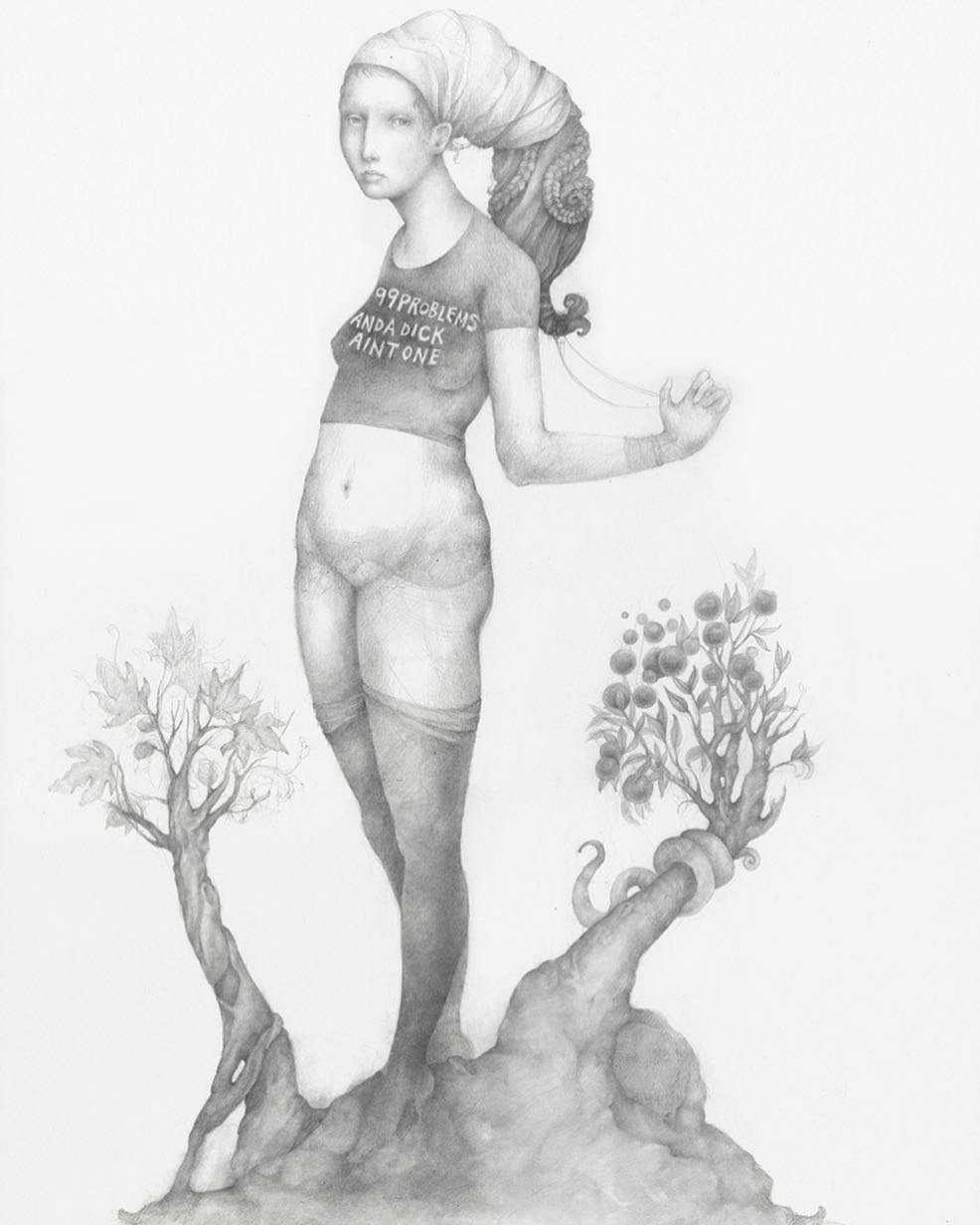

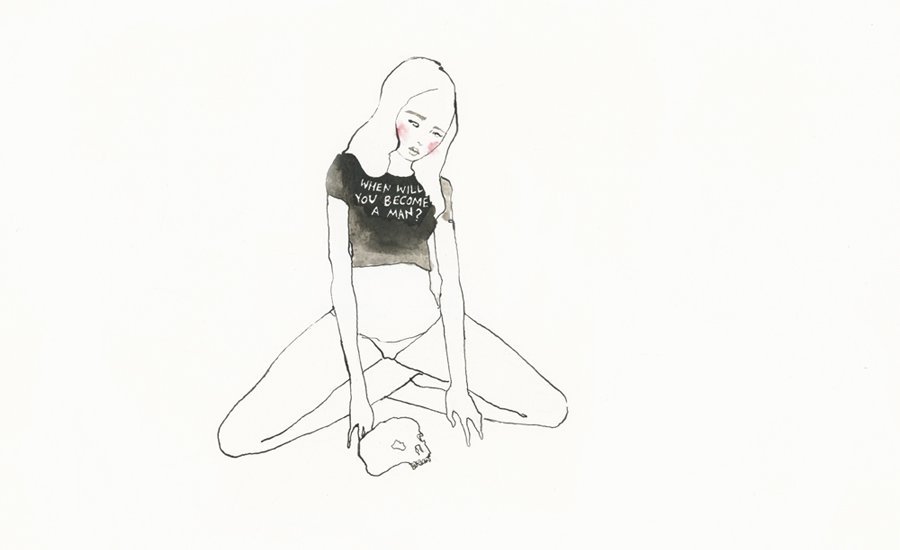

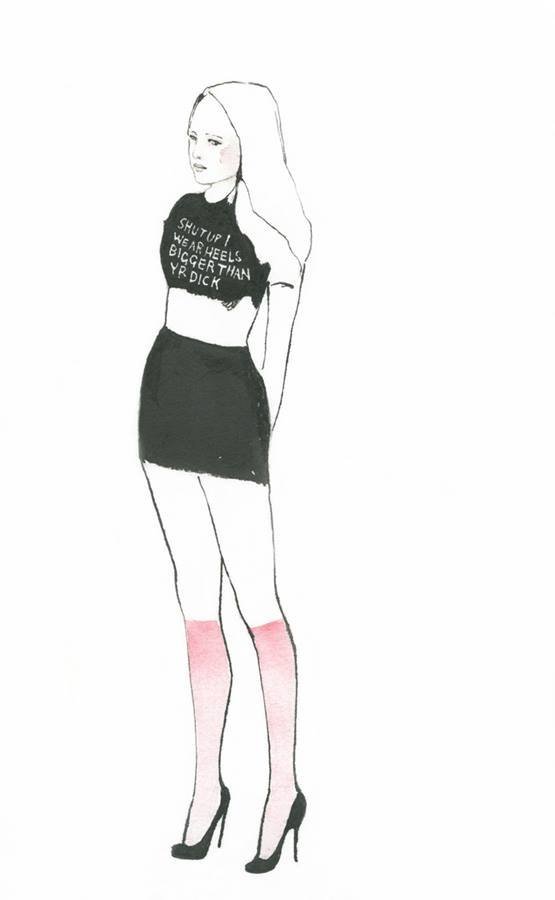

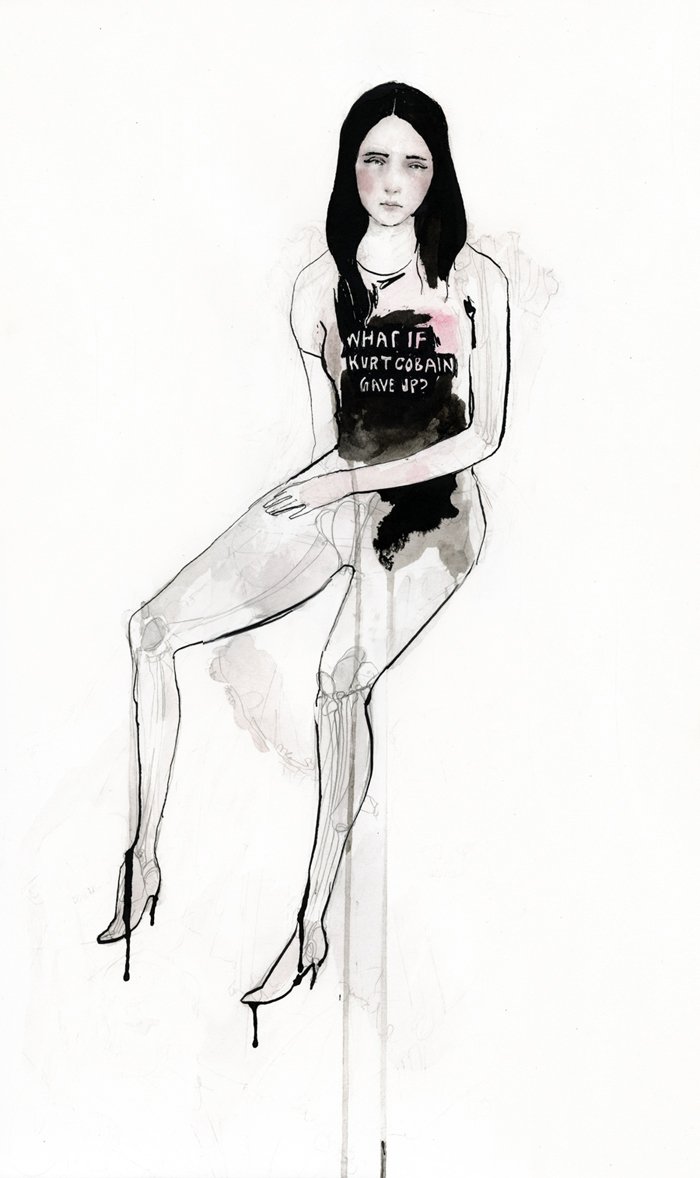

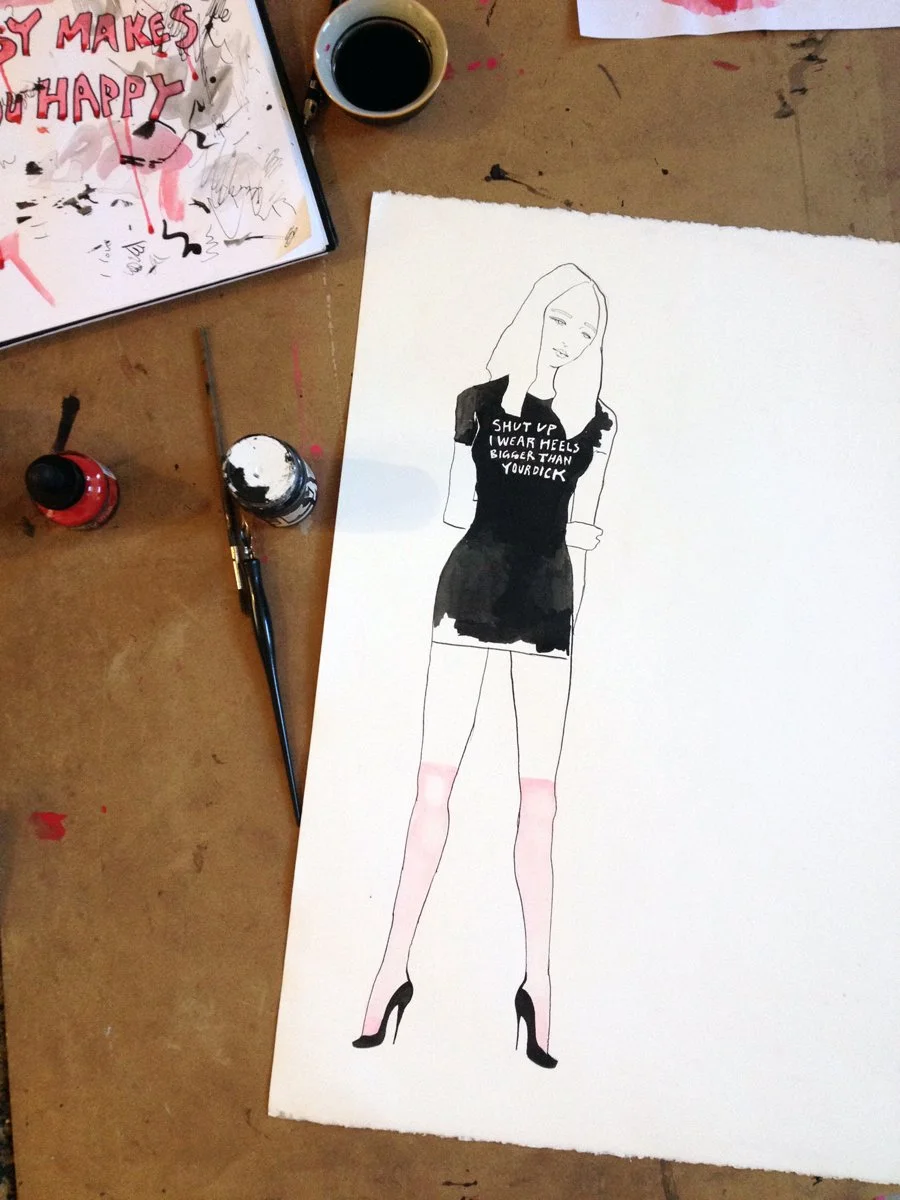

T Shirt Girls, 2015-2018 | Iterations on the trope of text on t-shirts as medium and message. (For Not Mom Material tee, go here.)

AMANDA MANITACH ON PAINTING, FEMINISM, WHISKEY AND T-SHIRTS

Published on New American Paintings, 2014

Knowing what to expect from Amanda Manitach is a tricky endeavor. The Seattle artist, writer and curator has linked the goring of a matador to menstruation, through imagery of red platform stilettos and dripping shards of beets. She has embroidered lambs’ tongues with clusters of tiny, antique beads, discarding the meticulously renedered work upon completion. She draws and paints works on paper that fuse classical nudes, horses detailed with prominent genitalia and melancholic ghost figures. But, a pair of legs in black stilettos walk behind the lamb tongue scene, and the tongue’s bulbous shape billows like the clouds that tint her watercolors, amending the surprise that the abrubpt shifts within her body of work evoke with the sense that perhaps we should have seen this coming, after all. A similar sensation continued in my conversation with Mantiach on her new show, T-Shirts, at Seattle’s Joe Bar, during which we discussed Instagram inspiration, third-wave feminism, sex murder, and the time she lied about her relationship with painting. – Erin Langner, Seattle Contributor

***

Erin Langner: While there have been some constant themes among your works on paper—the female body, sex and sexuality, states of being—the technique and style have varied. In the past, some of your drawings had a more ethereal, historically stylized sensibility. The works in T-Shirts and your recent New Works show at Bryan Ohno Gallery have a bold directness and a more stark, contemporary feel. What brought about that shift?

Amanda Manitach: Two things: I’m self-taught and easily bored. If I find a different style or medium suits an idea, I don’t feel beholden to old work. (I think it drives some collectors a little crazy). Before my show with Bryan, he threw down a gauntlet—he said I should make a big, sexy self-portrait. I thought that idea was dumb at first, but then, as an act of defiance, I got out my watercolor paints that same night and made a hyperbolic, nine-foot-wide, nude self-portrait, with my body draped François Boucher-style across a blue, velvet chaise lounge. It was the first time I’d ever done something that direct with paint.

Ninety-nine percent of the time, I freehand everything; I don’t work from photos or other sources. Watercolors and ink aren’t very forgiving, so if I hesitate, I’ll fuck up. I completed that self-portrait in one four-hour session of nonstop movement and bated breath. One sloppy stroke and the whole thing is toast (and a hundred dollars worth of paper wasted), so I was on pins and needles. It felt action-painter-y for the first time ever. The speed and physicality involved were intoxicating.

EL: That is interesting because a few years ago, in The Stranger, you were quoted as saying you do not paint.

AM: When I said that, it was partly a lie. I’ve always dabbled in watercolors. But I also always thought of it as auxiliary to drawing. Like hand-tinting: a blush, a hint of skin tone. When I had the show at Bryan Ohno Gallery, for the first time ever, I thought, Gee, these are straight up paintings.

EL: Text and narrative fragments appear regularly in your work, and you often mention literature among your influences. What attracted you to t-shirts as a vehicle for text?

AM: I follow some girls on Instagram who model for clothing companies, like Nikki Lipstick and WhoCaresNyc?. It caught my attention, this throwback/mashup culture tapping into goth-stoner-club, kid-kawaii looks from the 90’s. A lot of the messages on the clothing are nasty and hilarious and provocative, but in a way that’s...how do I put it? It probably serves you best to be young and cute and white to wear this stuff and have it come off as punk or subversive. It’s a kind of privilege.

Around the time I was getting obsessed with this, the gallery I curate (Hedreen Gallery) was hosting a bunch of events to examine the implications of being a female artist in Seattle in 2014, as well as the overall current state of feminism in the arts. The use of language surrounding feminist dialogue came up a lot. It’s a problem. Confusion of terminology and meanings seems to systematically undermine an understanding of collective goals.

You can see how this might have dovetailed into the t-shirt thing. Thinking about slut-shaming and slut-loving and the continued reclamation of dirty language sixteen years after the publication of Cunt. Thinking about how different privilege affords different feminists different uses of language, not to mention a sliding scale of efficacy and agency—especially when this kind of third-wave, fuck-you, self-objectification is at play.

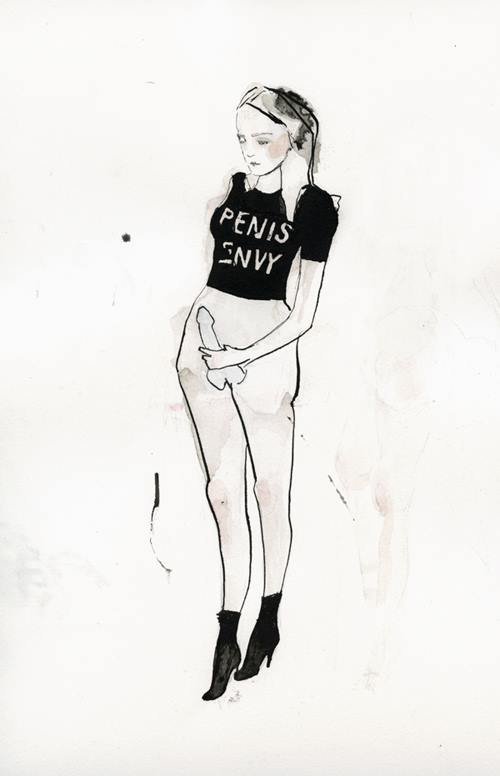

The first t-shirt drawing I made around this time was an ink drawing of a girl with a giant, erect penis and a t-shirt that said, “PENIS ENVY.” I thought it might piss off a few people, since it’s glorifying the phallus and all, but I’m a proponent of gender fluidity. I grew up very tomboy and I really wanted a dick as a kid, so it was true to me. The response was nuts. A lot of women loved it and identified with it, for a wide variety of reasons.

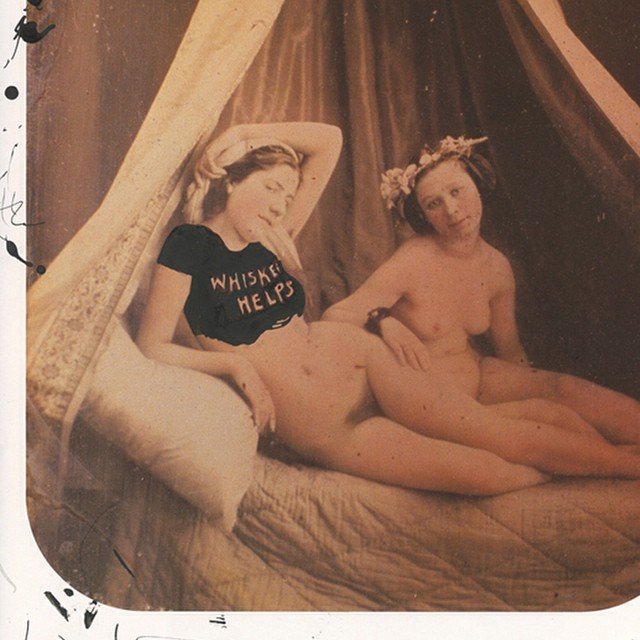

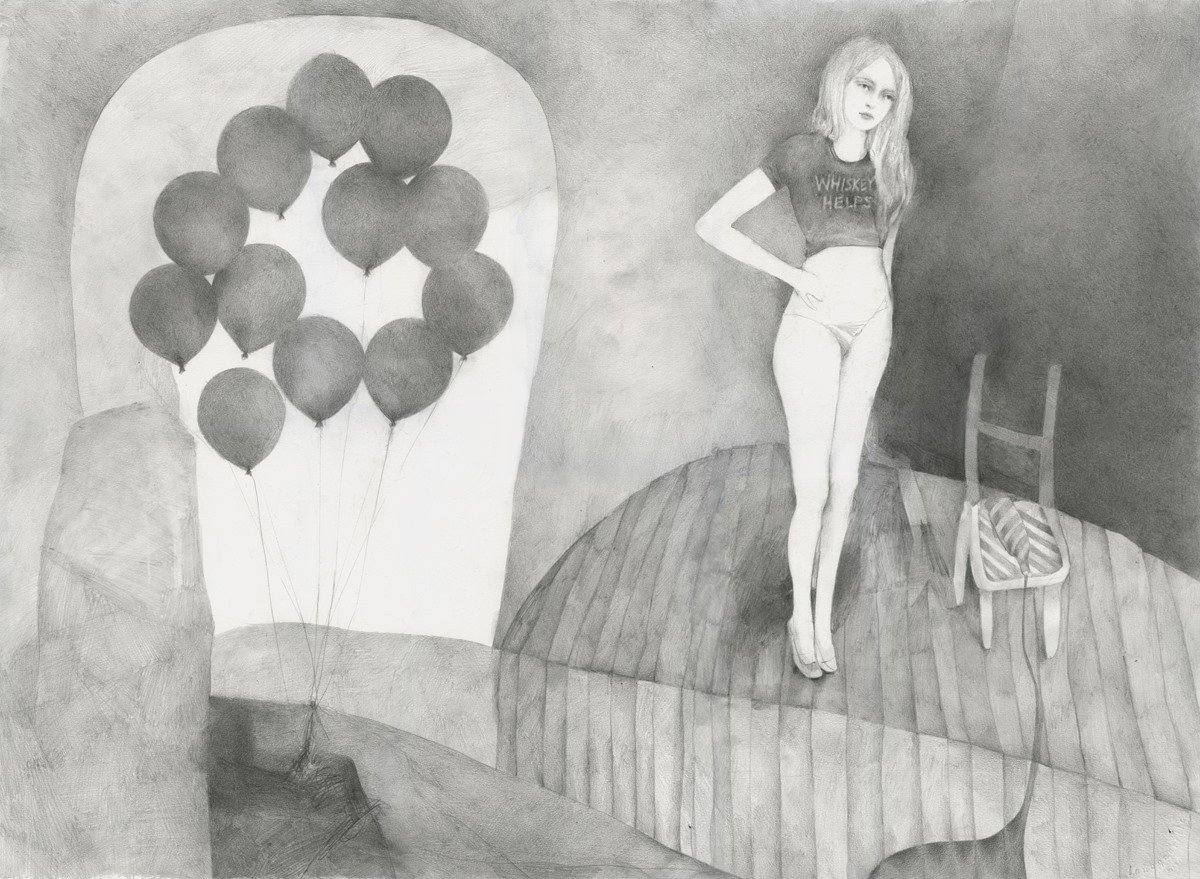

I continued from there with the t-shirts. I’ve sourced phrases from all kinds of places. I got “WHISKEY HELPS” from my boyfriend, who left that comment on Facebook in response to a religious relative, who was bellyaching about all of life’s little hardships and longing for heaven. I almost died. Hard but true.

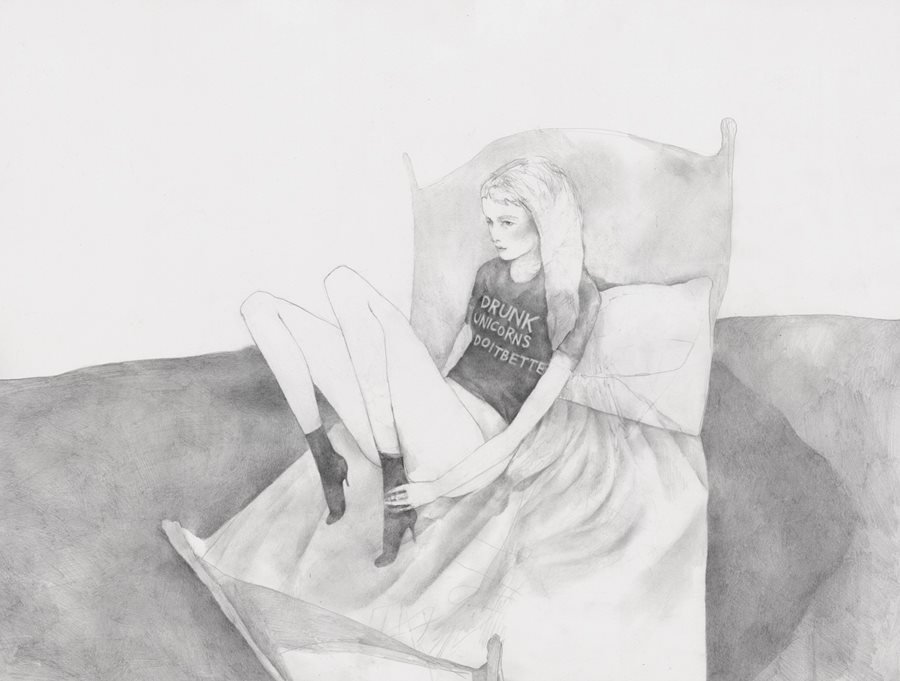

EL: Speaking of hardness, the softer, sensual sense of fantasy some of your works initially evoke is often counteracted by a kind of tangible, harder reality. In T-shirts, that dynamic comes through when the ghost-like figures cohabit the scenes with the t-shirt girls, but also in the more subtle ways that sex and sexuality are portrayed. For instance, the provocative poses the women assume nod towards the fantastical imagery and performative elements of sex, but they are tempered by facial expressions of ennui and the subtext of disappointment embedded within the t-shirts’ innuendos. Would you say this series tends more towards one side or the other—fantasy or reality?

AM: I would say reality. Granted, in the places where figures have literally been erased and barely cling to the paper, the situations represented become increasingly indeterminate. A lot of these scenes are aping either classic odalisques or early twentieth century Lustmord (sex murder) paintings by German painters like Otto Dix and George Grosz, except with the roles reversed, so that the woman isn’t the victim. Hence jokes like, “KILLER PUSSY.” But the girls aren’t quite femme fatales. There’s a grim sense that no one is exactly winning. Maybe that’s my cynicism coming out, in terms of how I feel about feminist discourse. Or about having a dick or not having one. One thing that’s definitely not fantasy: whiskey helps.