CITY ARTS, JUNE 2014

by Amanda Manitach

City Arts Magazine, June 2014

Sometime in the late ’70s—the exact date is fuzzy—a group of around 50 artists are seated on bleachers along the perimeter of a large room on the ground floor of the Oddfellows Building, where Oddfellows Café is today. The lights are out. Everyone is waiting for the performance to begin.

When Alan Lande finally makes an entrance, he’s holding a lit 60-watt light bulb in his hand, a long length of wire coiled on the floor at his feet. He begins to swing the bulb over his head. As the bulb picks up speed, Lande lets more cord slip through his fingers, little by little. The bulb spins faster and faster, etching a blinding circle of light in the black space. Faster and faster. By now Lande has let out 12 feet of wire, almost skimming the audience. The bulb circles so fast that it’s no longer legible as an object, apart from the hypnotic whizzing line of light burning into every retina.

Without warning, an accomplice planted in the audience holds up a floor-length mirror. The light slams into it, shattering the mirror and showering the audience with hot, sizzling shards of glass. Everyone’s suddenly wide awake.

At that moment, artist Ries Niemi was sitting next to Matthew Kangas, a writer who’d go on to become one of Seattle’s celebrated art critics.

“He was outraged, shaking and sputtering,” Niemi says. “Not a good review for that one, as I recall.”

The performance was part of an exhibit presented by and/or, an artist-run collective that operated in Seattle from 1974–1984. Lande’s light bulb stunt was one of hundreds of events that took place in the gallery that occupied 1525 10th Avenue. For almost eight years, the and/or space hosted a wild array of art—bizarre and risky, good and bad alike.

Pioneers of video art such as Nam June Paik, Bill Viola and Joan Jonas exhibited there. The gallery mounted Gary Hill’s first West Coast exhibition and showed early video work by Chris Burden. Punk poet and writer Kathy Acker lectured there; experimental composers Meredith Monk and Terry Riley played music there. Artists who fill art history books—Judy Chicago, famous for her seminal feminist artwork The Dinner Party; John Baldessari; Robert Irwin, Laurie Anderson and Vito Acconci—passed in and out of the Oddfellows Building (and often out into the streets, wherever performances meandered). The incomplete list of artists spans nearly 800.

That staggering number is only part of the largely untold history of the project, but it suggests the scale and ambition of and/or, a collective built on equal parts naïveté and sheer energy. It filled the halls of the Oddfellows with massive yurts and constellations of twinkling cathode ray tubes, and later gave birth to many of Seattle’s enduring arts organizations. As the buildings of Capitol Hill rise and fall and rise again, the energy of and/or lingers.

The person behind the visionary madness was Anne Focke, an artist and leader whose legacy on Seattle’s arts community is profound.

Even as a kid, Focke always jumped in to fill a void. Her high school in Ventura, Calif., didn’t have a marching band, so she started her own majorette group. Focke grew up in a handful of southern California cities before landing a scholarship to study art at Lewis & Clark College in Portland. But after two years of school, she itched for a bigger city, anonymity, adventure.

“Lewis and Clark was so far out that bus service stopped at 7 at night, so I hitchhiked,” she says. “I remember coming back to the dorm and people asked how I got there and when I said I’d hitchhiked, they lost it.

Focke transferred to the University of Washington and graduated with the first class to earn a degree in art history. She was hired as an assistant for the educational program at Seattle Art Museum, which led her to get involved with television and video production. Focke had never been on TV before but she jumped in, conducting live interviews with local artists for a half-hour arts magazine that aired on Channel 9. Believing that artists themselves should have access to cameras and editing facilities, she convinced the station to give them free reign. Once a week in the evenings, when no one was around, friends and colleagues invaded the studio to make experimental abstract videos that Focke produced, stuff like Tinseltown Review with Ze Whiz Kidz, a glammy drag comedy troupe. (“The station was probably covered in leftover glitter after those nights” she says.) These collaborations were the seed of and/or.

In the mid-’70s, Seattle’s art scene was built on a perfect storm of a terrible economy, cheap rents and a swell of homegrown artists who didn’t leave town after graduating high school. The euphoria of suburban homeownership had most people in its grip, leaving downtown and Capitol Hill rich in empty storefronts and residences. A four-bedroom Victorian on 13th and Pine cost $250 a month. An artist studio in the Pike/Pine corridor—engulfed in auto shops and fraternal lodges—cost around 25 bucks a month. Focke rented a makeshift studio in a basement on the same block as the Comet, which she shared with a musician, a sculptor and a handful of other artists.

Rooted on Capitol Hill, Focke had her eye on the East Coast and the new crop of alternative, artist-run spaces like the Kitchen, founded in New York in 1971. These unconventional places filled the gap between institutional and commercial venues for artists and championed newborn genres like video art, performance and installation. By the end of 1973, with the help of local arts patron and collector Anne Gerber and artists Bert Garner, Ken Leback and Jerry Jensen, Focke devised a plan for an artist-run space of their own. With a loan from her father (who offered his children modest sums to help purchase their first homes) and money from her job at the Arts Commission (which eventually became the Office of Arts & Culture), Focke rented out the storefront at 1525 10th Avenue and planned her first exhibit.

And/or opened on April 21, 1974—the 12th anniversary of the Space Needle. Called The Space Needle Collection of the Seattle Souvenir Service, the inaugural exhibit displayed approximately 380 Space Needle-inspired artworks and souvenirs. A six-foot-tall Space Needle made of fruits and vegetables loomed at the reception.

The programming that followed at and/or defied categorization. Focke and the small band of staffers built out a space to accommodate artist workshops and lectures, along with an electronic music studio and equipment for video and film production. The central gallery hosted monthly exhibits of work that didn’t have a home anywhere else in Seattle: conceptual pieces, correspondence-generated work, installations (called “environmental art” at the time) and, of course, video.

A year into its existence, and/or caught the eye of David Ryan, assistant director of the National Endowment for the Arts’ museum program, who was visiting Seattle from D.C. After Ryan insisted Focke apply for NEA funding, and/or received $10,000, which Focke put to use flying in artists from around the world.

“At that time, the international art scene was tiny and accessible,” Niemi says. “You used to be able to buy this booklet called Art Diary that had the phone numbers and addresses of artists. Famous artists. You can still get it, but you don’t get Jeff Koons’ cell phone number. In those days you did. You could just send a letter to someone and they would most likely respond.”

Visiting artists crashed on Focke’s couch for the night, then performed in the gallery to an audience of 50 or so people, or maybe 10. Laurie Anderson, not yet widely known, performed to a small handful of insatiable regulars, most of whom would relocate to the Comet in the wee hours of the night. Fluxus founder George Maciunas and Marcia Tucker, the Whitney curator who was about to launch New York’s New Museum of Contemporary Art, gathered around pitchers of beer with Focke and Niemi and the and/or faithful. For a moment, the international art world converged at 1525 10th Avenue.

Niemi recalls the night Charlemagne Palestine, a contemporary of Philip Glass and Steve Reich known for minimalist, droning piano compositions, filled the gallery with his slow-building wall of sound.

“Palestine had a deal with the Bösendorfer piano company that anywhere in the world when he played, they would arrange for an Imperial Bösendorfer , which has 97 keys, to be there for him,” Niemi says. “So some local piano company delivered a Bösendorfer to and/or and Palestine decorated it with his stuffed animals and a glass of cognac, lit up a kretek [clove cigarette] and proceeded to play Strumming Music for 45 minutes. Only a few people in the whole world have ever had that experience, but that sort of thing happened at and/or all the time.”

With continued funding from the NEA, and/or rented out more spaces in the Oddfellows Hall. Focke and friends installed walls within the ground floor to make office space (though the Comet would always informally remain the staff lounge). They created a library and resource center for artists, filled with otherwise inaccessible arts periodicals and a newfangled Xerox machine—which proved too expensive to maintain and eventually had to go. They co-opted the Century Ballroom, stripping the cavernous space and painting it stark white. And/or music director David Mahler collected enough gear in the music studio that he moved it upstairs to its own room in 1977. The studio centered around a vintage Buchla synthesizer and a four-channel tape deck. Musicians and composers rented the space for a dollar an hour.

When Focke discontinued exhibitions in the gallery in 1981, the side projects took on a life of their own, with and/or as their financial sponsor. The collective took on new projects, too: Artech, a commercial fine arts handling service, cared for and installed artwork (and still does so today); Spar, a contemporary arts magazine, ran from 1981–1982; CoCA, the Center on Contemporary Art, has presented exhibitions in various spaces for 30-plus years; and the artist-run media center 911 Media Arts continues to provide classes and access to media equipment today.

But so much improvisational growth and unfettered diversification—the spirit that made and/or thrive—also took its toll. Throughout its life, the group published a monthly newsletter called and/or notes, a hodgepodge of reviews, letters to the editors and gallery promotions. By 1980, the notes betray tension around the direction of and/or. They also outline concern that newly elected President Ronald Reagan would do away with the NEA altogether. At that point, Focke held a position on the NEA’s Visual Arts Policy Panel, and she reported on the national political shift directly from NEA meetings.

The NEA continued and so did and/or. In 1983, the group received one of its largest grants yet, a $25,000 Advancement Grant, which it planned to use to purchase space in the Oddfellows Building—but the transaction never went through.

Focke was struck: It was time to move on. “I felt it would be best to close the door and let something else emerge,” she says.

In late 1984, Focke coaxed and/or’s board of directors to discontinue use of the and/or name. In her notes to the board, she recommended a deliberate, public shutting down that would “allow and/or to end, to exist in a particular time period and not continue in the vague, unclear way it does now; free divisions to separate themselves from the history; be a good excuse for a party.” Instead of sparking a frenzied power grab, the end of and/or was characteristically fruitful. Focke convinced the NEA to let and/or keep the Advancement Grant even though they were officially shutting down. She used the money to distribute grants locally, launching the funding organization that is now known as Artist Trust.

During the 10 years it operated, and/or raised more than $1.5 million from the NEA as well as a grab bag of matching funds, garage sales revenues, membership dues and City and State grants. Focke used the money to fund some 600 public events and distributed $100,000 to artists.

Forty years after the inception of and/or, Focke lives in an apartment on Capitol Hill not far from the studios and storefronts her community once called home. On a sunny day in June, she’s visiting artist Norie Sato’s light-saturated studio in Ravenna to scavenge half a dozen boxes of archives filled with and/or notes, copies of Spar, calendars and exhibit catalogs. Sato, one of the earliest and/or members and staffers, balks at the leftover sheets of press type they used to painstakingly rub on the covers of the periodicals.

They rifle through boxes, ephemera flowing everywhere like a time capsule exploding.

“Wow, we did all that?” Focke says, dazzled.

They come across a program for an installation by San Francisco-based Terry Fox. It was a piece on labyrinths and meditation and involved a mass of melting candles.

“We had quite a few pieces that involved fire,” Focke says with a laugh. “It’s one of the things that keeps me from remembering.” But she does remember Lande’s exploding bulb performance. “He did some crazy things. Of course it wasn’t all crazy. There were gorgeous, subtle pieces too.”

And/or was a zeitgeist unto itself—not ahead of its time or of its time, but operating on its own logic of playfulness and defiance of limits. Somewhere, buried in the cracks between the time-weathered floorboards in Oddfellows Café, are cold slivers of light bulbs and mirror glass and dribbles of candle wax, like pieces of history nestled in the here and now.

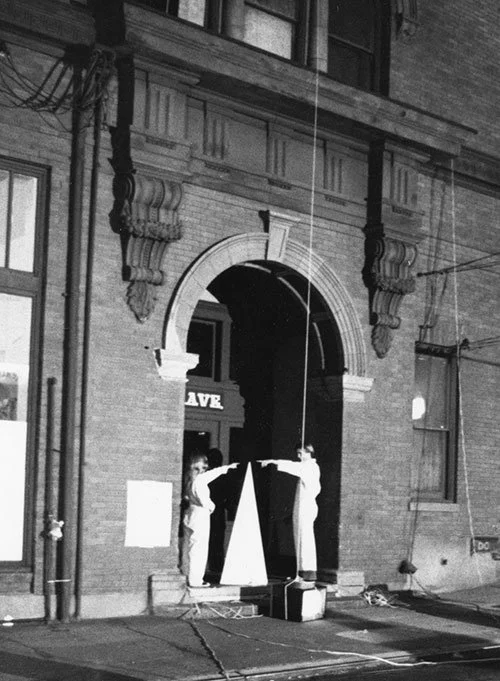

Pictured above: Capitol Hill’s 10th Avenue is shut down while Lori Larsen and Alan Lande perform on the steps of and/or. Photo courtesy of University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections, 36292.